David Carteau, Isabelle Pianet and Dario M. Bassani

Institut des Sciences Moléculaires, CNRS UMR 5255, Université Bordeaux 1, 351 Cours de la Libération, 33405 Talence France. E-mail: [email protected]

Introduction

Memories of summer vacations on the Mediterranean would not be complete without recollections of the refreshing anise-flavoured alcoholic beverages served during the hot afternoons. Though varying in name and composition across cultures (Raki in Turkey, Arak in Lebanon, Ouzo in Greece, Sambuca in Italy and Pastis in France), extracts from star anis (Illicium floridanum) are a common principal ingredient of the plant extracts used in their production. Besides their pungent anis aroma, another well-known trademark of these drinks is their transition from a clear solution to an opalescent milky-white substance when they are diluted with water. This sudden change in physical appearance will not go unnoticed by a scientist, who may summarily assign it to the precipitation or separation of the hydrophobic organic fragrances due to the addition of water. We know this not to be entirely correct,1 however, as it should lead to a rather un-appetising biphasic mixture in which the essential oils would float on top of a large volume of water and alcohol. The truth behind this apparently simple phenomenon is actually much more complex—and very interesting indeed!

The principal component extracted from star anis is trans-anethole (E-4-methoxyphenylpropene, t-A), which is a naturally-occurring flavouring compound present in numerous essential oils, including fennel, star anis and aniseed. One of the most intriguing properties of t-A, however, is its capability to undergo spontaneous emulsification upon rapid dilution of a concentrated solution with a miscible but non-solubilising solvent. This phenomenon, for which the term “ouzo effect” has been coined by some authors,2 is responsible for the cloudy aspect of the above-mentioned beverages as the alcohol content of the hydro-alcoholic solution is dropped from above 40% to ca 5% v/v and affects the photochemistry of t-A.3 Self-emulsification phenomena are the subject of continuing investigation due to their importance in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries, and yet more applications, such as the formation of nanoparticles and nanocapsules, are emerging.

In the case of t-A, dynamic light scattering (DLS) and small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) techniques have been employed to elucidate the origins of the self-emulsification process.4 However, to obtain information on the origin of the droplets formed at the initial stages of emulsification, it is necessary to employ techniques that are capable of directly monitoring the exchange between the free (dissolved) and the aggregated fractions of the immiscible component. For this, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is particularly well adapted as it is capable, in favourable cases when the individual components possess different spectral signatures, to directly monitor the exchange between molecules that are in different environments.5 In many occurrences, however, the NMR spectra of emulsions are not very informative due to inhomogeneous line-broadening of the signals. Surprisingly, this is not the case for emulsions of t-A in water, though, as convincingly shown in Figure 1. The sharp and clearly distinguishable signals are attributed to t-A located in different environments: a moderately polar aromatic environment within the aggregates, and a hydrophilic aqueous phase. Because the exchange between these two environments is much slower than the frequency difference of the chemical shift of the protons, the resultant spectrum shows a sharp signal for each proton in either of the environments.

The possibility of following spectroscopically the occurrence of t-A in the aggregated and aqueous phase simultaneously opens exciting possibilities for further elucidating the emulsification process. For example, the quantification of the component in each phase—a sometimes inextricable problem—becomes trivial and can be performed in real-time, limited only by the rate of data acquisition of the spectrometer. But NMR spectroscopy can do so much more than take simple 1H spectra! By using specific pulse sequences, for example, it is possible to generate spin populations whose exchange and decay can be followed. In this particular study, the use of exchange spectroscopy (EXSY) and diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) proved particularly useful to characterise the kinetics of the exchange of t-A between each sub-phase, and the growth of the aggregates, over time.

Methods

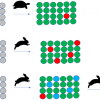

The EXSY (Exchange SpectroscopY) NMR experiment is a powerful methodology to investigate exchange processes in molecular systems under a dynamic equilibrium.6 The principle is relatively simple: radiofrequency pulses are applied to create a magnetic non-equilibrium between exchanging species in chemical equilibrium. It is the subsequent return to the magnetic equilibrium, which is under the influence of the chemical exchange, that 2D EXSY NMR permits one to observe in a particularly vivid representation. Let us take the case of a system in which two compounds are in exchange: free t-A resonating at ω1 and aggregated t-A resonating at ω2. The NMR sequence (Figure 2A) is composed of a first 90° pulse that creates the transverse spin magnetisation. In the course of the following evolution period t1, the transverse magnetisation vectors evolve at their characteristic resonance frequencies (in our case ω1 for free t-A and ω2 for aggregated t-A) and become “frequency labelled”. The exchange process predominantly takes place after the second 90° pulse, which replaces the magnetisation along the z axis (longitudinal magnetisation) during the mixing time period tm. The last 90° pulse is named the “reading pulse”, and rotates the magnetisation in the x–y detection plane. The signal is recorded all along the t2 period during which the magnetisation components precess at their new resonance frequencies owing to the exchange process. The experiment is then repeated for a number of equally spaced values of t1, and the result is a data matrix s(t1, t2) for which a double Fourier transform gives a 2D spectrum S(ω1, ω2). The appearance of an off-diagonal peak at frequencies ω1, ω2 in the 2D spectrum indicates that exchange occurs between free t-A and and aggregated t-A.

The DOSY (Diffusion Ordered SpectroscopY) NMR experiment is a method that gives rise to the measurement of a translational diffusion coefficient (D), and thus allows differentiation of species based on their diffusion in solution. The NMR pulse sequence, that was proposed by Stejskal and Tanner in 1965,7 is based on a spin echo sequence in which two magnetic gradient pulses G, of δ duration and separated by a delay Δ, are inserted during the echo periods τ (Figure 2B). At the beginning of the experiment, the net magnetisation is oriented along the z axis and the 90° pulse rotates the magnetisation in the “reading plane” x–y. At a time point t, a pulse gradient of δ duration and G magnitude is applied, and at this time each spin experiences its particular characteristic phase. Then two scenarios are possible. If no diffusion occurs, the 180° pulse cancels the effect of the two gradient pulses and all the spins will refocus leading to a maximum signal at the echo (i.e. at the end of the second τ period, see Figure 2B). But if the spins have moved during the Δ delay, the degree of dephasing will be proportional to the displacement of the spin during this delay, inducing an attenuation of the signal. The greater the diffusion, the larger the attenuation of the echo signal. This is illustrated in Figure 2B (right) in which the signal of free t-A is more attenuated than the aggregated t-A.8

Results

Figure 1 shows a proton spectrum of t-A obtained approximately 10 min after emulsification. According to expected pattern for the proton spectrum, two distinct sets of readily assigned resonances can be distinguished, suggesting that t-A can exists in at least two forms. Three types of NMR experiments confirm that these two forms correspond to free and aggregated t-A. First, EXSY experiments acquired on the mixture clearly demonstrate a slow exchange between the two species, confirming that the same compound is undergoing exchange between two states. Second, DOSY experiments performed on the mixture show that the two species have very different diffusion coefficient values: about 6 × 10–10 m2 s–1 and 1 × 10–10 m2 s–1 allowing the unambiguous assignment of the free and the aggregated forms, respectively, as shown in the DOSY spectrum displayed in Figure 2. Third, proton spectra recorded at different ethanol concentrations (up to 60% ethanol) show that only the free form of t-A is present in solutions containing >40% ethanol.

When water is added to an alcoholic solution of t-A, the mixture instantaneously takes a cloudy aspect that appears visually stable for at least six to eight hours, after which creaming can be observed. This stability, however, is only apparent: Figure 3 displays the 9-CH3 signals acquired over the course of time. It shows that while the intensity of the free form (∂ 1.78) remains constant, the signal assigned to the aggregated form (∂ 1.39) decreases with time. This decrease can be quantified thanks to the presence of a small amount of methanol (5 mM) added to the mixture as an internal standard. From these results, it is possible to deduct the proportion of t-A which is invisible by NMR (Figure 3B). After 40 min, the latter plateaus at 3.5 mM, which represents ca 70% of the total t-A concentration. At the same time, the proportion of small aggregates decreases to a concentration close to 0.7 mM whereas the proportion of free t-A (which is determined by its solubility in the hydroalcoholic solution) remains constant (0.8 mM).

The fraction of t-A not visible in the NMR proton spectrum recorded using classical liquid techniques is assigned to t-A present as small droplets that are several micrometres in size and that are responsible for the cloudy aspect of the solution. In agreement with this assignment, their concentration can be fit to a monoexponential function that is consistent with an Ostwald ripening process. This behaviour is typical of droplet growth and agrees with previous investigations of t-A droplets by Grillo et al.4 using small-angle neutron scattering.

In the case of t-A emulsions, EXSY NMR experiments allow one to observe the exchange of magnetisation between the free and the aggregated forms: such an exchange is adequately described by the bimolecular process illustrated in Figure 4, which assumes that the observed rate constants ka and k–a are pseudo-first order rate constants that depend on the concentration of free t-A and t-A present in small aggregates, respectively. Following the evolution of ka and k–a over time (Figure 4) shows that two growth regimes are present. At early times, ka is greater than k–a and the population of small aggregates is growing. After ca 1.5 h, k–a becomes greater than ka, implying that the small aggregates are now dissolving. This can be understood by taking into consideration the formation of the larger droplets, which are now growing by Ostwald ripening at the expense of free t-A in solution. This, in turn induces the preferential dissolution of the smaller aggregates due to their higher ratio of surface area to mass.

Conclusion

Taken together, our findings indicate that the initial steps of the spontaneous emulsification of t-A are, in fact, somewhat more complex than previously thought. A model emerges in which small, nanometre-sized aggregates are initially formed upon rapid dilution of more concentrated hydroalcoholic solutions. These then slowly disappear in favour of the larger droplets previously observed by light scattering experiments. While using dynamic NMR spectroscopy to follow emulsification phenomena may appear counter-intuitive, we hope this study serves to demonstrate the contrary: it is a wonderful technique that offers enormous potential to obtain high-quality information not otherwise available. The principal conditions for its applicability are that the exchange between species be slow on the NMR timescale, and, of course, that the experimentally-accessible concentration range be suitable for NMR spectroscopy. Cheers!

References

- D. Carteau, I. Pianet, P. Brunerie, B. Guillemat and D.M. Bassani, Langmuir 23, 3561 (2007).

- S.A. Vitale and J.L. Katz, Langmuir 19, 4105 (2003).

- D. Carteau, P. Brunerie, B. Guillemat and D.M. Bassani, Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 6, 423 (2007).

- N.L. Sitnikova, R. Sprik, G. Wegdam and E. Eiser, Langmuir 21, 7083 (2005); I. Grillo, Coll. Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 225, 153 (2003).

- D. Carteau, D.M. Bassani and I. Pianet, C.R. Chimie 11, 493 (2008).

- J. Jeener, B.H. Meier, P. Bachmann and J. Ernst, J. Chem. Phys. 71, 4546 (1979).

- E.O. Stejskal and J.E. Tanner, J. Chem. Phys. 42, 288 (1965).

- S. Balayssac, V. Gilard, M.-A. Delsuc and M. Malet-Martino, Spectrosc. Europe 21(3), 10 (2009).